Milk must sour

Week 6: the one with a beer brewing nun

For the next ten weeks, I’m letting go of control to see where trust and curiosity might take me. This week I found myself in Bavaria, sharing beer and bread with Germany’s last beer brewing nun.

Have you ever wondered what the kitchen of a German beer-brewing nun looks like? If you guessed white lace curtains, dated wooden cabinets, and a grand collection of ceramic Bavarian beer mugs, I’d owe you a high five and a puzzled look. Because you’d be eerily correct.

Schwester Doris Engelhard is a living legend in the beer world. In her seventies, she has brewed it all but drinks only the good stuff. The first time I ever laid eyes on her was on a laptop screen, when a friend showed me her Munchies interview. In it, a somewhat timid interviewer trails after Sister Doris while she fires off one-liner after one-liner. “Beer makes you beautiful,” followed by, “Your belief must be strong if you believe that water is healthy!” and ending with my personal favorite: “If Christ was Bavarian, he would have drunk beer instead of wine.” You can imagine that when I got the offer to tag along for a visit to the good sister, I didn’t even have to summon the power of surrender. I immediately said yes.

The drive toward the Mallersdorf Abbey proved long and bumpy. A broken AC, combined with a fever that wouldn’t budge, left me a sweaty, dizzy pile of limbs as the car wove its way through northeastern Bavaria. Six weeks of floating from country to country, waking up in a different bed day after day, had left me worse for wear.

It was a relief when I saw the monastery. It lay on top of a small hill, stark white and very German. No frills, spotless, and extremely functional. We found Doris after receiving extensive directions from a large blond man lugging crates of beer into a truck. “Sie ist da,” he said while pointing at a wooden door. Not a lie was told, because seconds later, a short woman dressed in a blue apron and white headpiece stepped out. Her handshake was firm, her eyes sharp and inquisitive. She led us straight to the beer cellar, where she fished out a couple of chilled half-liters.

Five words and twenty-five steps later, I found myself parked on a stern wooden kitchen chair while Sister Doris placed a glass in front of me. I couldn’t suppress a gleeful squeal as I popped the top and quickly poured the ice-cold Helles. She herself drank from a clay mug with a hinged lid, which she snapped open with her thumb in a way that made her look part nun, part cowboy. We clinked our glasses, her smiling face beaming back at me both from across the table and from the label on the bottle.

The official business that led us to her monastery was dispatched within minutes. It was clear she would much rather talk about what she loved most: beer.

“Small traditional breweries like mine are dying out,” she sighed, topping off her mug. “I refuse to pasteurize my beer. It kills the flavor.” She tapped the neck of the bottle for emphasis, as though daring it to contradict her. Customers, she explained, shy away from her brews’ shorter shelf life. “People have grown too used to food that never perishes. All these artificial preservatives, it’s wrong. Milk must sour. Butter must turn. Cheese must mold.”

I nodded solemnly, though in my mind I pictured the tub of margarine back home that had survived two breakups and a global pandemic. It dawned on me that she wasn’t just talking about beer; she was talking about the scandalous truth that things are supposed to go bad.

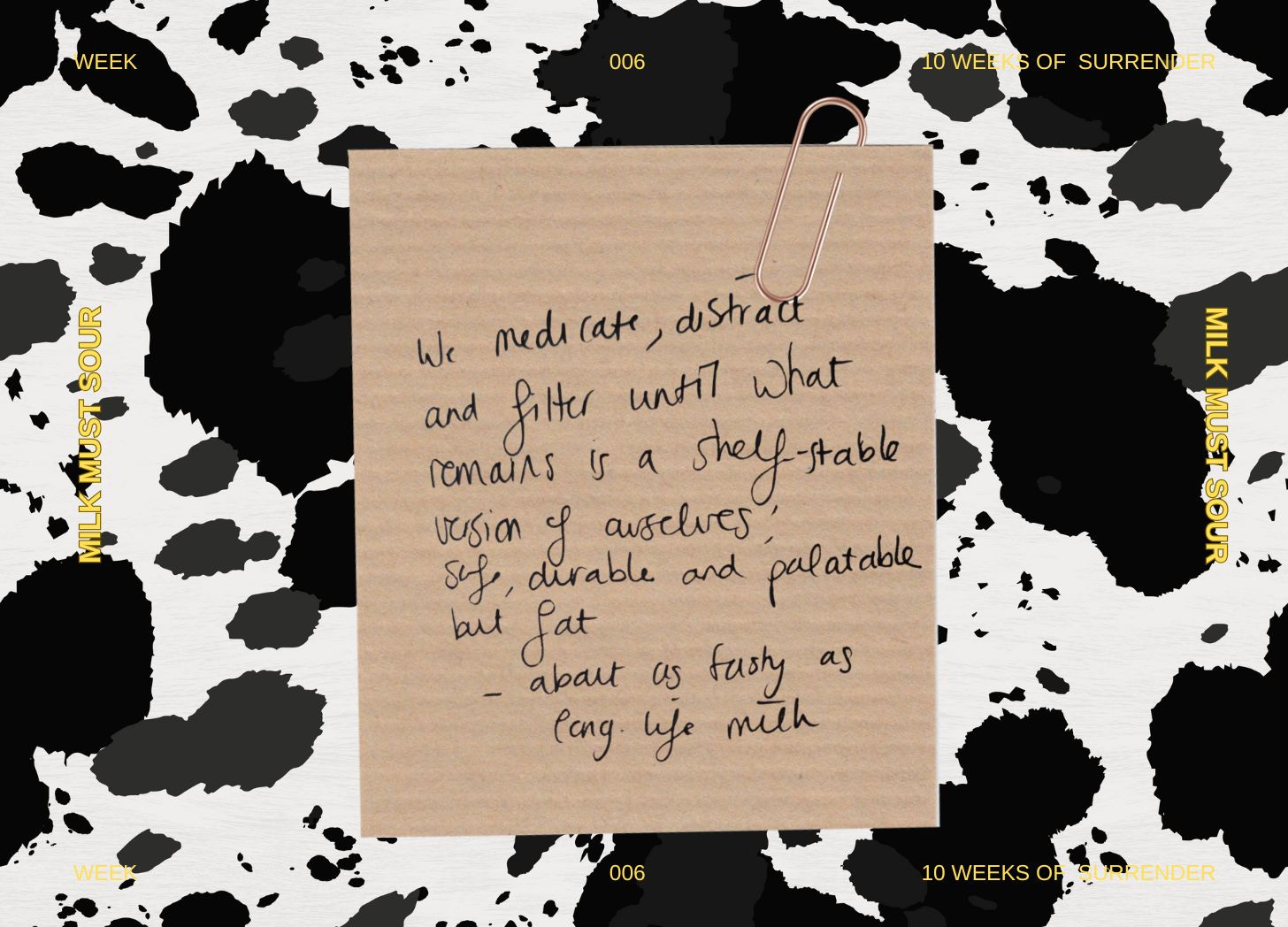

And the longer she talked, the more it hit me. We haven’t only pasteurized our food, we’ve pasteurized our lives. Fairy tales still promise “happily ever after” as though happiness were some kind of permanent residency you could secure with a mortgage and a university degree. Sadness is treated like a system error, grief as a broken appliance, suffering hidden as though an embarrassing rash. We medicate, distract, and filter until what remains is a shelf-stable version of ourselves: safe, palatable, but flat. About as tasty as long-life milk.

Doris chuckled then, shaking her head as if the whole world had gone mad. “Beer that never spoils,” she said, “isn’t beer at all.” I smiled meekly, for her words lodged deeper than I expected. It was part joke, part sermon. What makes her beer worth savouring is that it doesn’t last forever. What if the same goes for me?

What if the sour notes—the pain, loss, illness, and heartbreak of the past few years—aren’t failures but the yeast, the funk, the bitter edge that proves my life has depth. Yes, life without suffering might keep longer, but would I even want to drink it?

When we finally left the monastery, we had sampled every beer in Doris’s arsenal. Luckily, the thick slices of monastery bread, accompanied by a suspiciously gray tub of pâté, had kept me from staggering through the courtyard on the way out. The sun was slipping behind the hills, turning the white walls of the chapel to gold. My fever had returned with a vengeance, leaving my clothes stuck to me like plastic wrap. I knew the drive back would be just as long, hot, and airless as the one here. And yet, somehow, this time I did not mind. Even this, with my head pounding and my body aching, felt like part of the taste of things.

We made one last stop in the cellar to load up on a few crates. Since we now had the perfect excuse to drink them quickly, we slipped in a few extra bottles. Just then Doris pressed a small bundle into my hands. On top of a stack of leaflets and beer coasters was a sticker. Doris’s face grinned up at me, mug raised triumphantly, with the word “Religion” printed next to her left ear and “Rocks!” next to her right.

I thanked the Schwester in my best German, and as she slowly closed the heavy monastery gates, I climbed into the back of the car. I stared at the sticker and couldn’t suppress a smile. Indeed, Doris. Your love for all that perishes, your religion, rocks. To be alive, she showed me, is to risk spoiling. And that, I realized, is exactly why it tastes so good.

I love Doris